Solidarity in Bath is about positive action to address homelessness, poverty, marginalisation and voicelessness.

It’s 2023 and people are sleeping rough and begging on the streets of Bath. The large number of empty shops and unused properties in Bath are a stark visual insult to citizens who have to live, and die, on the streets: in a city of abundant wealth and resources this is absurd.

Solidarity in Bath is not about communism, socialism or any other ism.

Solidarity in Bath is about embodied closeness to each other. It is about awakening agency and celebrating the interconnectedness of us all. It is about compassion and empathy and finding time and space to act in support of each other.

Solidarity in Bath is an invitation to follow the calling that emerges from seeing people suffering. And it is an invitation to refuse to look the other way, or comfort ourselves in the belief that someone else is going to care.

We are doing something very simple: we are sitting on the streets of Bath with people experiencing street homelessness giving soup, companionship and the occasional fiver. We are sitting with compassion and respect in our hearts. We are talking. But mainly we are listening and the stories we hear are powerful: they have potential to liberate us all. On the streets we hear stories of resilience, suffering and transformation. A new story is emerging to challenge the usual narratives around homelessness and precarity: a new story to dissolve some of the barriers experienced by marginalised groups; a socially-just story where the voices of people experiencing homelessness, poverty and institutional discrimination speak their truth to power.

Aims

- Act in solidarity with people experiencing precarity using mutual aid practises

- Highlight and challenge systemic relationships that perpetuate precarity and marginalisation

- Strengthen and build cultural narratives and practises that support agency and belonging for everyone

180 years ago Charles Dickens beseeched us that “we should make some slight provision for the poor and destitute”. And it was 180 years ago that Scrooge washed his hands of his individual obligation with the excuse that the state provided what was needed. When people are forced to sleep on the streets their needs are clearly not being met.

We all wish that no one was homeless and there is a lot of kindness shown to people on the streets. But we wash our hands of people experiencing precarity when we out-source our individual agency to the state. We tell ourselves comforting stories about precarity and homelessness: maybe we believe the problems faced by those on the streets are too big to deal with, or that they should dust themselves off and get a job, or that they are being cared for by some charity? Such narratives often do not match the reality on the streets. Similar narratives are handed down to us by those with voice and power but those with voice and power have little insight into the plight of those who live at the margins of our society: trickle-down ideologies, like trickle-down economics and trickle-down care has been trialed for a long time and has failed many of our citizens. It’s time for care from below and it’s time to ask a new question about precarity and homelessness: when it comes to social inequality, what if poor people aren’t the problem? (McGarvey, 2022).

Solidarity in Bath is about inverting the dominant narrative which has often blamed poor people for their poverty. Such a narrative would have us believe that people on the streets are lazy, feckless and work-shy. Enquiries into the lives of poor people frequently make such claims, where their habits, ways of life and coping strategies are blamed and their ingenious survival strategies ignored or penalised (Vincent, 1991). Narratives or ‘regimes of truth’ (Foucault, 1977) that are based on the premise of victim blaming are constructed by the winners, but when the social-contract is framed from above it is always biased and the myths of meritocracy and individualism enshrined in neoliberal thinking (McGarvey, 2022) have made it easier than ever to blame the victim.

Blaming the poor for their poverty is an abusive historical trope: it is wrong and must stop.

Solidarity in Bath is about challenging the impact of trickle-down thinking at its root level by elevating the voice of marginalised people in order to correct the distortions inherent in the dominant narrative. Solidarity in Bath is about finding a new way of belonging and allowing those who find themselves homeless a place to belong. Solidarity in Bath is an invitation to challenge the preconceptions we hold about precarity through a new emphasis on the voice’s of the poor. The seemingly intractable issues of poverty, marginalisation and voicelessness are under scrutiny (Radio 4, Start the week, 13-05-2022).

Our culture is at a turning point and the direction of our collective future is in our hands.

The deep inequality we see on the streets affects us all and hurts us all in a variety of physical (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009) and psychological ways: “greater inequality heightens social threat and status anxiety, evoking feelings of shame which feed into our instincts for withdrawal, submission and subordination: when the social pyramid gets higher and steeper and status insecurity increases, there are widespread psychological costs.” (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2019).

When you live on the streets you are marginalised in a multitude of ways. People living on the streets often experience extreme levels of judgment, rejection, defamatory stereotyping, outright prejudice and violence and often have literally no place to belong (Heap, Black & Devany, 2022 and Oliveira, 2018).

We know that personal growth is facilitated by empathy, unconditional positive regard and authenticity in relationship to others (Rogers, 1967) yet people on the streets often experience the opposite of this from passers-by and from the institutions which are supposed to safe-guard them. It would challenge any of us to exist on the streets in similar circumstances: would the intense marginalisation and precarity on the streets lead to feelings of helplessness and worthlessness, to feeling like you had no place to belong, to an abdication from culture, to a learned helplessness, to an abandonment of any feelings of agency, to anger, to frustration and embitterment? If you stop and speak with someone on the streets with empathy and compassion you will encounter someone who is struggling but you will also encounter an individual who, on an hourly basis, surmounts and rises above precarity and the shame heaped upon them by our culture.

The humanity of people on the streets shows us that someone lacking all the basics (shelter, warmth, bodily security, sleep, food and belonging) can be, spiritual, enlightened, compassionate, moral, spontaneous and artful. The paring away of resources often comes with profound insight into self and other, into what matters and what does not matter. These insights are valuable and badly needed if our culture is to heal some of the fractures it is experiencing.

A new approach to care, belonging and precarity is possible: an approach that is less pathologising and meets people where they are at; an approach to belonging and social provision that does not place itself above those it serves because it values and prizes the contribution and healing those experiencing precarity can bring into all our lives.

Gabor Maté (2019; 2022) argues that our culture caters to our needs little better than a zoo caters to the needs of its inmates. Solidarity in Bath is about creating more room in our individualist ego-centric culture for greater empathy, less blame, and a wider acceptance of peoples’ difficulties. What if we saw homelessness as a symptom of a sick system and the experience and knowledge of people experiencing precarity as a valuable wake-up call for a system spinning out of balance?

Solidarity in Bath is about facilitation of agency, for having a belief in what one is doing is one of the main reasons anyone can do anything. McGarvey, (2022) in his recent Reith Lecture on the ‘freedom from want’, invites us to walk hand in hand with those less well off to support them to regain agency. The obstacles to personal agency for people living on the streets are so many that those who can must walk alongside them while they regain their feet. In doing this we may also find that something is awakened in ourselves as the genealogy of the knowledge and power systems (Foucault, 1977) around us becomes more discernible.

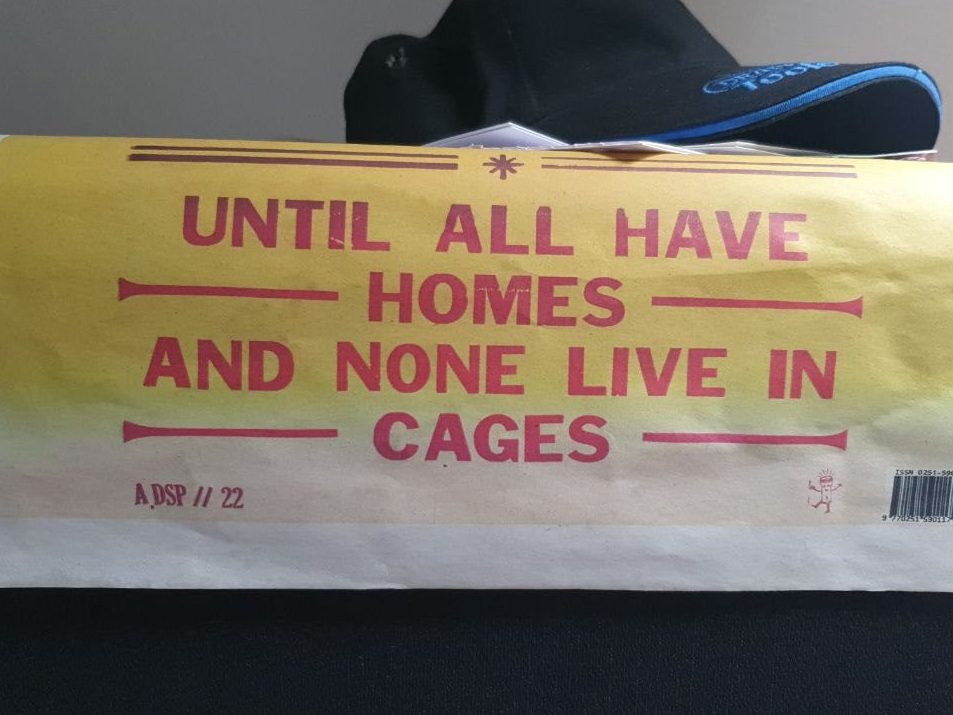

We are on this journey together and your support is welcome. We are not claiming to have the answers and the issues of homelessness and precarity are complex. On the streets, issues of personal autonomy or agency collide with structural and interpersonal oppression. Solidarity in Bath is about facilitating personal responsibility as much as it is about challenging structural, systemic and interpersonal constraints: both are needed, for all the agency in the world is of no use if you are trapped in a cage. Where individual agency is possible, solidarity in Bath is about nurturing and scaffolding that, and when the individual finds themselves with little they can exert control over due to structural factors, solidarity in Bath is about challenging those restraints.

Next time you are in Bath, challenge your perceptions of people living on the streets by sitting down to speak to them, by opening your heart to them. The mere act of sitting with a person experiencing homelessness visibly bridges the gap between the homeless citizen and shows solidarity is available to us all. To sit on the street with someone experiencing homelessness is to do a simple yet powerfully subversive act. It takes a little courage to take the first step, but once done, a tentative reconciliation is built between our heads and our hearts, between the stories we tell ourselves and reality, between ourselves and others and with practice that may become a firm bridge to inclusivity for all.

The opposite of entitlement is gratitude and the route to gratitude is perspective. Sitting in solidarity on the streets provides perspective and that perspective may liberate us all.

References and sources of information

Dickens, C. (1843). A Christmas Carol. Chapman and Hall

Glover, R. (2015). Foucault -The Genealogy of Power and Regimes of Truth, Glover, R. Lecture 12: YouTube link

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin.

Heap, V; Black, A & Devany, C. (2022). Living within a public spaces protection order: the impacts of policing anti-social behaviour on people experiencing street homelessness. Sheffield Hallam University.

Lawlor, L. & Nale, J. (2015). The Cambridge Foucault Lexicon. Cambridge university Press, online version only: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-foucault-lexicon/truth/FA3484B4BEDE31D2D1C2F01BAE265CEB#

Maslow, A, H. (2017). A theory of human motivation. Wilder Publications.

Maté, G. (2019). Feel Better, Live More. https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/feel-better-live-more-with-dr-rangan-chatterjee/id1333552422?i=1000515090871

Maté, G. (2022). The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture. Vermilion.

McGarvey, D. (2022: 13th June). BBC Radio 4, Start the week: Social inequality up close: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m00187fm

McGarvey, D. (2022: 17th June). BBC Radio 4, The social distance between us. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001887j

McGarvey, D. (2022: 14th December ). BBC Radio 4, Reith Lecture on Freedom from Want. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m001g2zf

Oliveira, B. (2018). On the news today: challenging homelessness through participatory action research. Journal of Housing, Care and Support. VOL. 21. pp. 13-25, © Emerald Publishing Limited.

Rogers, C. (1967). On becoming a person. Constable and Company Ltd.

Vincent, D. (1991). Poor Citizens: The state and the poor in twentieth century Britain. Longman Publishers.

Wilkinson, R & Pickett, K. (2009). The spirit level: why greater equality makes societies stronger. Bloomsbury Press.

Wilkinson, R. & Pickett, K. (2019). The inner level: how more equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and improve everyone’s wellbeing. Penguin Books.

Quotes

A human being is a part of the whole, called by us, “Universe,” a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest – a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to the affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature and beauty. Nobody is able to achieve this completely, but the striving for such achievement is in itself a part of the liberation and a foundation for inner security.

Albert Einstein (1950)